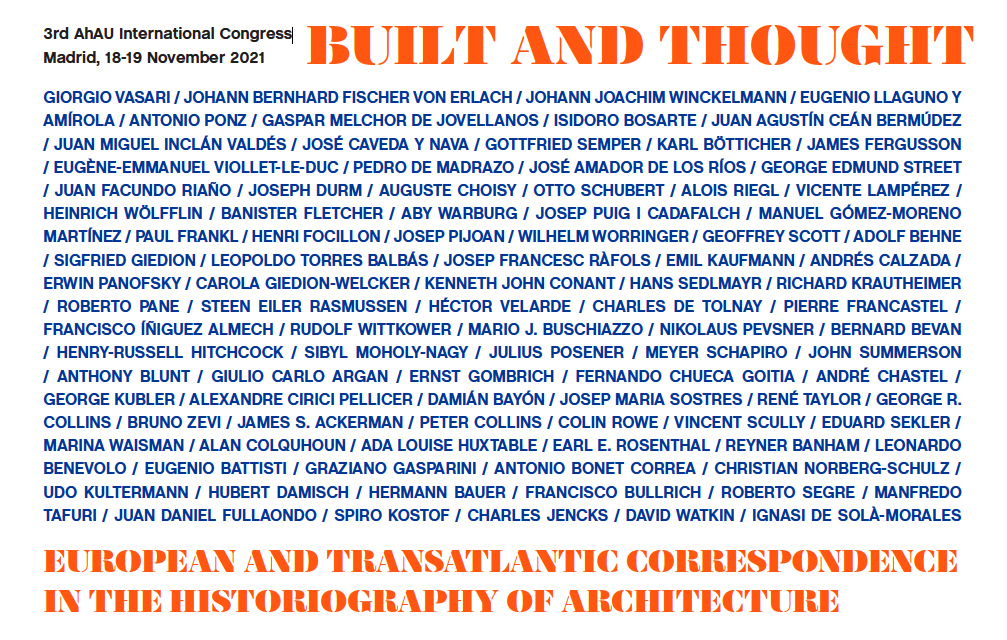

BUILT AND THOUGHT

EUROPEAN AND TRANSATLANTIC CORRESPONDENCE IN THE HISTORIOGRAPHY OF ARCHITECTURE

PDF – 3rd AhAU International Congress

All histories of architecture are products of an intellectual construct. As such, they are circumstantial discourses, developed from particular provisional points of view, chosen from a range of possibilities. From Giorgio Vasari’s The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects to Manfredo Tafuri’s historiographic project, every generation has read on the past from the angle of the problems specific to its period. // In the time that has elapsed from Renaissance humanism to our days, from what perspectives, and with what reach, has architecture history been formulated? One of the main challenges of this encounter is to trace the construction of the history of architecture. // What is the purpose of architecture history? Since the Renaissance and into our days, architecture history—often written by architects—has been at the service of a professional practice seeking legitimation. This course of action, however, has become useless, and more so in a changing world like ours, where historians, in their eagerness to break with univocal interpretations, do not wish to judge the past nor impose irrefutable truths, but to question them. // From what positions can the history of architecture be constructed nowadays? Meanwhile, the historiography of architecture is seen as an incomplete, unfinished project where there is an unavoidable need, on one hand, to preserve the objectivity required of all scientific procedures, and on the other hand to incorporate the new paradigms of our times. Simultaneously, it is necessary—more now than ever before—to orient the work of architectural historians around its potential to lay down problems, rather than around achievements and successes, and in the spirit of formulating a body of knowledge that will benefit society, in our case mainly through research and teaching, but also through dissemination, so that the knowledge does not stay within its traditional closed circles. // The congress endeavors to be an opportunity to reflect on the historiographic construction of architecture from inside and outside at the same time; that is, to meditate on the discipline itself, but in terms of the challenges and currents of thought that characterize the contemporary world and today’s culture, ultimately with a view to constructing a new history.

Sir Banister Fletcher, “The Tree of Architecture”, 1921.

… there are, dear reader, two kinds of Histories;

those that have happened, and those that have been thought about

Juan Caramuel, Architectura civil recta y obliqua (1678), II, V, 29

DIRECTORS

Salvador Guerrero, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid.

Joaquín Medina Warmburg, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology.

SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE

Juan Calatrava, Universidad de Granada / Julio Garnica, Universidad Politécnica de Cataluña / Salvador Guerrero, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid / Jorge Francisco Liernur, Universidad Torcuato di Tella / Joaquín Medina Warmburg, Karlsruher Institut für Technologie / María Teresa Muñoz, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid / Carlos Plaza, Universidad de Sevilla / Eduardo Prieto, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid / Delfín Rodríguez, Universidad Complutense de Madrid / Josep M. Rovira, Universidad Politécnica de Cataluña / André Tavares, Universidade do Minho-Dafne Editora.

OPENING AND CLOSING LECTURES

Historiography of architecture in the age of humanism.

Fernando Marías, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid-Real Academia de la Historia.

Historiography of architecture in the machine age.

Jean-Louis Cohen, Université Paris VIII-Institute of Fine Arts, New York University.

THEME PANELS AND LECTURERS IN CHARGE

1. From great narratives to microhistory: genres of architecture history.

Delfín Rodríguez, Universidad Complutense de Madrid.

To look at writings on architecture history and study the relationship that exists between their content—including their more or less explicit ideological presuppositions—and their form is to analyze the underlying tensions between the singular and diverse or between the particular and universal. Also to explore the opportunity to formulate architecture history in the manner of great narratives or microhistories, or a fusion or hybrid thereof. The aim is to understand how form and content—genres and ideologies—interrelate and condition the objectives and development of the historiography of architecture.

2.- Masters and disciples: historiographic generations.

Julio Garnica, Universidad Politécnica de Cataluña.

If we take the generation concept as that which agglutinates individuals who identify with one another through age similarity and shared cultural parameters, we can say that every generation has a time and space dimension that formulates its particular questioning of the past, and thus also its particular contribution to the revision of historiographic traditions. Each generation also establishes a particular relationship with those that precede and succeed it; a master-to-disciple transversal relationship of capital importance in the passing down of knowledge. Generational affiliations and conflicts are interwoven in this process, chaining certain authors to others as well as to their respective historiographic schools.

3.- Archaeologies of knowledge: the historian as bricoleur (materials, techniques, and tools).

Josep M. Rovira, Universidad Politécnica de Cataluña.

The intellectual contributions of the Belgian anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss—in Wild Thought (1962), with its bricoleur figure— and the French philosopher Michel Foucault—in The Archaeology of Knowledge (1969), with its focus on “discursive formations” and “order of discourse”—profoundly transformed historiographic thought models. How do we transfer these reflections to the historiography of architecture given its heterogeneous and incomplete materials—vestiges of past experiences—and its ambition to create a new discourse?

4.- Inside and outside the canon in the historiography of architecture.

María Teresa Muñoz, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid.

Writing or telling the story of architecture involves selecting experiences and works that provide the keys to the historical narrative, prioritizing certain criteria and leaving aside others. Ingrained here of course are value judgments where architectural quality has often weighed less than narrative potential; a capacity, that is, to be of use in interpreting the past. Because of this methodological bias, many works of true worth have been relegated to a place of oblivion on the grounds of being difficult or even bothersome, contradicting the hegemonic (and almost always teleological) readings of history.

5. Operative historiographies: disciplinary tool versus intellectual activity.

Carlos Plaza, Universidad de Sevilla.

The Italian architectural historian Manfredo Tafuri first used the expression “operative criticism” in 1968 to explain the instrumental relationship between architecture history and the project. Nevetheless, for Tafuri the practice of criticism was “to catch the historical scent of phenomena, to put them through the sieve of strict evaluation, show their mystifications, values, contradictions, and internal dialectics, and explode their entire charge of meanings.” The conflicting positions trace the conceptual arc by which the historiographic discourse of architecture has taken shape.

6. Intersecting histories: national constructs and international networks.

Juan Calatrava, Universidad de Granada.

At least since the late 18th century, narratives of architecture history have been instrumental to the construction of national discourses and identities. At the same time, the transnational nature of architectural phenomena has led to parallel, intersecting, and interconnected narratives. The intellectual cosmopolitanism of historians has also played a part in encouraging the mixing of native and foreign in the deep structure of architectural evolution.

7. Invention of the Other: America and the Orient in historiographies of architecture.

Jorge Francisco Liernur, Universidad Torcuato di Tella.

The cultural construction of difference has been the object of numerous histories of architecture. The inventions of America and the Orient stand out as territories colonized by the cultural conquests of colonialism and Eurocentrism. We must now urgently subject such constructions to a revision, and build new narratives from multiple and diverse viewpoints that respond to current political and cultural challenges on a global scale.

8. Mass media: histories for consumption (travel guides, books, magazines, travel journals, film, radio, televisión, exhibitions, Internet).

André Tavares, Universidade do Minho-Dafne Editora.

We tend to take architecture history as a field of knowledge pertaining exclusively to academic environments. But the explosion of information and communication technologies in our contemporary world has had a formidable impact on architecture and its public presence, giving it new cultural, social, and economic relevance in sectors like communication media and tourism. This raises the question of the position that architecture historians ought to take between the high culture of academic discourse and the popular language of mass consumption.

9. Global, environmental, digital: new paradigms.

Eduardo Prieto, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid.

The revision of historiographic traditions often addresses a desire to adapt to prevailing conditions of the contemporary world; a yearning, for example, to better understand the origins of architecture’s current challenges, and with that, deal with them more efficiently. Globalization, digitalization, and environmental degradation are three of the challenges that force us to change the way we think of the world. That said, it seems important to rewrite or reinvent architecture history on the basis of the new paradigms.

30 September 2021: Last day for early registration with discounted fee

30 September 2021: Last registration day for those wanting their papers published in Proceedings

18–19 November 2021: 3rd AhAU International Congress.

Should the evolution of the pandemic render it necessary, the Association of historians of Architecture and Urbanism (AhAU) reserves the right to modify the above calendar.

Registration

Authors selected to present their papers orally or publish them in the Proceedings, and who are not entitled to a discount, should pay a registration fee of 160€.

The registration fee for members of the Madrid College of Architects (COAM) and for professors and researchers is 80€; and for students, 40€.

All three fees will be reduced by 20% if paid by 30 September 2021.

Organizer

Asociación de historiadores de la Arquitectura y el Urbanismo